This explainer clarifies the central focus of the Civilian Protection Monitor: civilian harm mitigation and response (CHMR). While CHMR activities can safeguard civilians and fulfill moral, legal, political and strategic imperatives for governments and militaries alike, CHMR stands at a crossroads in the face of political pressure and conflicts that push at international norms. Yet it remains more vital than ever.

Published: 25 April 2025. Author: Lucca de Ruiter

What is civilian harm?

Civilian harm refers to the negative impacts experienced by non-combatants during armed conflicts. Civilians can be harmed in numerous ways during conflict, including through deliberate harm by some militaries, but also by becoming caught in crossfire, airstrikes, and other military actions. The harm they experience includes physical injuries and death, but –crucially– also encompasses psychological trauma, loss of property, loss of access to education and healthcare, displacement, and other indirect and ‘reverberating’ effects. The destruction of infrastructure and essential services, for instance, can have long-term impacts on civilian populations. An airstrike that destroys a bridge may have direct deadly consequences for civilians in the vicinity – yet this may also have long-term consequences by cutting civilians off from access to hospitals, schools, and sources of livelihood across the bridge, exacerbating suffering and increasing mortality rates. If a family’s primary breadwinner loses a limb and is unable to continue working, the entire family may face poverty, which in turn can contribute to disrupted access to education for children and child labour. To truly address civilian suffering in war, a comprehensive view of harm is therefore crucial.

Common causes of civilian harm

Civilian harm often results from:

- Misidentification. Military actors mistake civilians or civilian objects for military targets. This can happen through:

- Misjudgement and confirmation bias: military actors assume militant status and see behaviours and patterns which could be explained otherwise as confirmation of military involvement. This is particularly likely to cause the death or injury of civilian, military-aged men.

- Misassociation: flawed intelligence leads to targeting errors, for instance when information on possible threats is matched to the wrong location.

- Automation bias: AI bias in military targeting can lead to the misidentification of civilians as combatants, especially when systems are trained on flawed or incomplete data. As AI accelerates the speed of targeting decisions, human control becomes less meaningful, increasing the risk of deadly errors driven by automation bias and overreliance on system outputs.

- The use of explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA). When explosive weapons are used in populated areas, schools, hospitals, homes, critical infrastructure and lives are destroyed. Many of these weapons were originally designed for use in open battlefields and are inherently indiscriminate when used in populated areas and therefore result in increased civilian casualties and devastating humanitarian impacts. This is particularly true for explosive weapons with a wide-area effect, such as weapons that are inaccurate (e.g., mortar fire), have large blast and fragmentation radiuses, and/or use multiple munitions across an area (e.g., cluster munitions). Roughly 10 percent of airstrikes fail due to weapon malfunctions, leaving behind unexploded ordnance, fragments, and other hazardous remnants in populated areas. These dangers can persist for decades, posing long-term risks to civilians and complicating post-conflict recovery.

- Inadequate planning. Failing to anticipate the presence of civilians or their movement in tactical and operational planning.

- Miscommunication at checkpoints. Civilians can face harassment, injury, or even death at military checkpoints due to misunderstandings, language barriers, perceived threats, or excessive use of force.

- Dual-use and collateral damage. Military attacks on civilian infrastructure are sometimes justified by claims that these places are being used by combatants. These sites are labeled ‘dual-use’ because they serve both civilian and military purposes. While this term has become common, international law does not formally recognise ‘dual-use’ as a legal category. However, over time, the growing use of the ‘dual-use’ label has blurred this distinction, putting civilians at greater risk. In addition, under International Humanitarian Law (IHL), armed forces may sometimes accept a certain level of civilian harm if that harm is considered proportional to the military advantage gained by the attack. As long as all practical precautions are taken to avoid or minimise harm, such ‘collateral damage’ can be legal—even if civilians are killed or injured. This means that not all civilian harm in war qualifies as a war crime.

According to recent data, misidentification and the use of EWIPA in particular account for a significant proportion of inadvertent civilian casualties in modern conflicts. Sadly, there are also belligerents who make little effort to avoid harming non-combatants or even purposely target civilians. Crucially, this does not relieve their opponents of their obligations under IHL to protect civilians.

What is CHMR?

CHMR refers to efforts to minimise civilian harm during armed conflicts and to address its consequences when it occurs. ‘Mitigation’ involves proactive measures, such as training troops to account for civilians during operations and careful planning to reduce the risk to civilians. ‘Response’ happens after harm has occurred, and includes providing acknowledgement and accountability, compensating or assisting affected civilians, as well as identifying and implementing lessons learned.

Why does CHMR matter?

- Moral reasons. Safeguarding human life and dignity is a fundamental ethical obligation. Civilians have a moral right to receive redress for harm caused to them, and to know the fate of their loved ones.

- Legal compliance. The laws of armed conflict, including International Humanitarian Law (which encompass the Geneva Conventions), requires parties in conflict to distinguish between combatants and civilians and to take all feasible precautions to avoid harm to civilians. Civilian harm can nevertheless occur within the bounds of IHL-compliant warfare.

- Political reasons. Civilian harm tracking and reporting is crucial for external oversight of military operations, enabling a comprehensive understanding of their impact. By implementing effective and transparent CHMR tools, legislative government bodies and the public can make informed decisions about adapting, halting, or ending military interventions.

- Strategic and operational interests. Causing civilian harm –and failing to account for this– can undermine the legitimacy of military operations. This, in turn, limits operational freedom of action, strains coalitions, fuels insurgencies, and damages relationships with local populations, ultimately prolonging conflict and instability. Furthermore, service personnel can also experience moral injury as a consequence of their involvement in civilian harm incidents. This risk is particularly acute when states refuse to acknowledge harm from their own military actions, making it more difficult for personnel to address their own experience and cutting them off from the required support systems.

- Military accuracy. A common cause of civilian harm is misidentification of targets. Therefore, investing in CHMR capabilities such as Pattern of Life Analysis also increases targeting precision, thus enhancing operational effectiveness.

While IHL provides the legal framework and minimal requirements for civilian protection, CHMR offers practical tools and strategies to protect civilians that often go beyond mere compliance with IHL. CHMR focuses on operational planning, improved targeting processes, and formalising processes for tracking harm, conducting assessments and investigations into harm allegations and providing amends. CHMR is also a key component of the broader Protection of Civilians (PoC) agenda, which encompasses a wide range of efforts to safeguard civilian populations during armed conflict. PoC emphasises not only the reduction of harm caused by an actor’s own military operations, but also protecting civilians from harm caused by other actors, and ensuring the provision of humanitarian assistance to those affected by conflict. While Protection of Civilians (PoC) and Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response (CHMR) are distinct frameworks, it is essential that states develop clear policies on both to ensure comprehensive safeguards for civilians before, during, and after conflict.

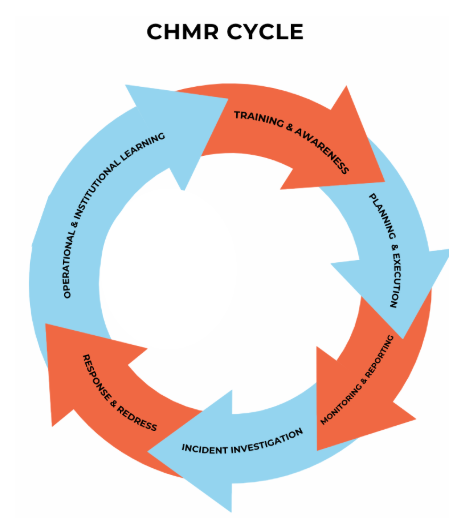

How does CHMR work?

Effective CHMR involves a combination of proactive and reactive measures, including:

- Training and awareness. Armed forces receive training on cultural sensitivities and civilian protection strategies such as tactical patience and determining civilians’ pattern of life.

- Planning military operations & tactical execution. Military forces analyse the operational environment to minimise civilian risk. This includes gathering accurate intelligence, avoiding populated areas when feasible, timing the operation to ensure there are no civilians present in an area, choosing weapons with reduced collateral effects, or warning the population before military action takes place.

- Monitoring and reporting. Systems are established to track and analyse civilian harm incidents to learn from mistakes and improve practices.

- Incident investigation. When harm occurs, thorough assessments and/or investigations are conducted to determine causes and accountability.

- Response and redress. Responses can include providing medical care, issuing apologies, compensation to victims, or reparative actions like rebuilding destroyed infrastructure.

- Operational and institutional learning. Using data from civilian harm tracking, assessments, and investigations to inform operational refinements to prevent or minimise causing harm in future actions.

→ Read this article by PAX for 10 common misconceptions about CHMR.

Conclusion

Civilian harm is an inevitable consequence of war, but its impact can and must be significantly reduced through effective CHMR practices. By prioritising civilian protection, governments and militaries can fulfill their moral, legal, political and strategic obligations. Public and civil society engagement plays a crucial role in ensuring that CHMR policies are implemented and strengthened, fostering accountability and a more humane approach to conflict, which is what the Civilian Protection Monitor is all about.